Positive: addition of

abnormal experiences

Delusions: (fixed belief unamenable to change) of grandeur or persecution etc.

hallucinations, (perception in the absence of external stimuli)

and disorganization in thoughts and speech (typically associated with psychosis), distortions of self-experience: (feeling one's thoughts aren't one's own.)

Negative: elimination/absence of

normal processes

These are also sometimes called the 5 A's.

Apathy

Avolition (lack of motivation especially for self directed purposeful otherwise routine behaviours)

Anhedonia (an inability to feel pleasure)

Asociality (lack of desire to form relationships)

Diminished Expression

Blunted Affect (reduced emotional reactivity)

Alogia (poverty of speech) mainly due to selective attention problems resulting often in a word salad.

Cognitive: Deficits in

normal cognition

they occur earlier than positive or negative symptoms and are more reliable indicators of functionality.

they can be both deficits of Neurocognition or Social Cognition.

70% prevalence

relapsing episodes of psychosis, distorted perception of reality, impairment in thinking, behavior, affect and perception.

Psychosis can be defined as the disturbance in determining between what is real and what is not (distortion of reality)

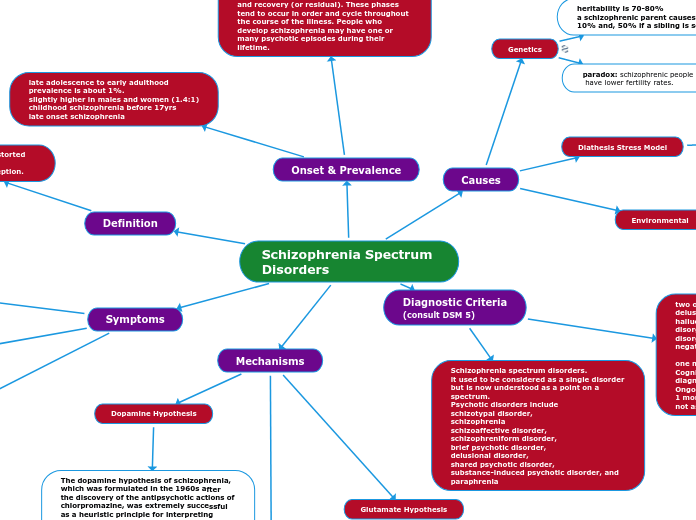

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

it used to be considered as a single disorder but is now understood as a point on a spectrum.

Psychotic disorders include

schizotypal disorder,

schizophrenia

schizoaffective disorder,

schizophreniform disorder,

brief psychotic disorder,

delusional disorder,

shared psychotic disorder,

substance-induced psychotic disorder, and paraphrenia

two of the following symptoms

delusions

hallucinations

disorganized speech

disorganized/catatonic behavior

negative symptoms

one must be from among the first three.

Cognitive symptoms aren't needed for a diagnosis.

Ongoing for at least 6 months with at least 1 month of active psychotic phase.

not associated with any other disorders.

Environmental

prenatal maternal distress

infections and medications

malnutrition

childhood trauma

50% of cases use recreational drugs

more prone to suicide

less responsive to treatments

Genetics

heritability is 70-80%

a schizophrenic parent causes chances to be 10% and, 50% if a sibling is schizophrenic

paradox: schizophrenic people

have lower fertility rates.

Diathesis Stress Model

The diathesis–stress model is a psychological theory that attempts to explain a disorder, or its trajectory, as the result of an interaction between a predispositional vulnerability, the diathesis, and a stress caused by life experiences

late adolescence to early adulthood

prevalence is about 1%.

slightly higher in males and women (1.4:1)

childhood schizophrenia before 17yrs

late onset schizophrenia

Phases of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia has three phases – prodromal (or beginning), acute (or active) and recovery (or residual). These phases tend to occur in order and cycle throughout the course of the illness. People who develop schizophrenia may have one or many psychotic episodes during their lifetime.

Prodromal Phase: During the initial onset of schizophrenia, there are barely noticeable changes in the way a person thinks, feels and behaves. For example, the person may start to perceive things differently, withdraw from others, become superstitious, work or study may deteriorate, and he or she can become irritable and have difficulty concentrating or remembering things. This phase usually occurs between ages 15 to 25 in males and ages 25 to 35 in females.

Acute Phase: During the next phase, clearly psychotic symptoms are experienced. The term “formal thought disorder” is often used as an overall term to describe these acute or ‘florid’ symptoms.

Recovery Phase: Following an active psychotic episode, florid symptoms recede and depression may develop as people regain insight into their behavior and begin to realize the impact the illness has had on their lives. For some people, residual symptoms may remain and their ability to function effectively can decrease after each active phase.

Dopamine Hypothesis

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, which was formulated in the 1960s after the discovery of the antipsychotic actions of chlorpromazine, was extremely successful as a heuristic principle for interpreting aspects of the phenomenology of schizophrenia. The development of improved antipsychotic medications was guided by a search for dopamine blockers based on the concept that schizophrenia is, in part, a hyperdopaminergic state.

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia postulates that hyperactivity of dopamine D2 receptor neurotransmission in subcortical and limbic brain regions contributes to positive symptoms of schizophrenia, whereas negative and cognitive symptoms of the disorder can be attributed to hypofunctionality of dopamine D1 receptor neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex.

The hypothesis was originally based on the observation that known psycho-stimulants, such as amphetamine, induce stereotypic motor behaviors. These behaviors could be blocked by antipsychotic medication, such as chlorpromazine, which by interfering with dopamine function was known to lead to parkinsonian-like movement disorders.

Glutamate Hypothesis

Glutamate is the major "excitatory" neurotransmitter in the brain, which means that it helps to activate neurons and other brain cells. About 60% of neurons contain glutamate, and virtually all of them have some type of glutamate receptor. Glutamate contributes to prenatal and childhood brain development, but one of its most important roles as people mature is in learning and memory. Glutamate is essential for "long-term potentiation," a process by which new information or skills are retained for later use.

The multiple areas of the brain involved in schizophrenia are connected by a circuit of brain cells that rely on glutamate to communicate. Research so far suggests that either excess or insufficient glutamate activity may cause symptoms, partly through its interactions with other neurotransmitters like dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

At least two major neurotransmitters appear to be involved in the pathogenesis of SZ. They are reflected in the dopamine and glutamate hypotheses of SZ. The historically older dopamine hypothesis of SZ presumes subcortical dopamine hyperfunction. Facts that support the dopamine hypothesis are: the clinical doses of antipsychotic medications are related to their affinities for the dopamine D2 receptor, the majority of SZ patients are supersensitive to dopamine activation drugs such as amphetamine and cocaine.

The glutamate hypothesis postulates disruption of excitatory neural pathways through NMDA receptor hypofunction. Facts that support the glutamatergic hypothesis of SZ are: NMDAR antagonists uniquely reproduce both positive and negative symptoms of SZ, and induce SZ-like cognitive deficits and neurophysiological dysfunction.

Recent research shows that the hypotheses are not exclusive. Indeed, there is a strong interaction between both neurotransmitter systems at the level of single cells and neural networks. In particular, dopamine and glutamate interactions at the frontal–basal ganglia thalamocortical pathways are involved in modulation of signal-to-noise ratios.